“Help: My bowel is leaking” – Leaky Gut Syndrome

Today’s article is about “Leaky Gut Syndrome (LGS)”. We will give you an overview of Leaky Gut Syndrome, possible causes, associated conditions, symptoms and treatment options. So, let’s get started!

Table of contents

Introduction/terminology/excursion into the medical study database PUBMED

What is Leaky Gut Syndrome? The term LGS refers to the so-called “intestinal barrier“. Most practicing physicians are not familiar with this term. When those affected report that they have increased intestinal permeability or LGS, they are usually not noticed or not taken seriously. Likewise, LGS is often dismissed as a medical pseudo-construct by complementary medicine practitioners. It is claimed that this is not scientifically proven that an LGS is a problem. I can clearly counter these statements here and say that this is not true. There are certainly many unanswered questions, but an LGS definitely poses a problem for the individual.

You can see this very quickly if you do some research and enter the term “leaky gut” in the renowned medical database collection PUBMED: 95 scientific publications(https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=leaky+gut). These deal primarily with the connection between a disturbed intestinal barrier and the development of autoimmune diseases, which cannot be denied, and other incredibly important topics that are increasingly becoming the focus of current medical research and discussion. Clinical reports suggest that LGS contributes to autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and celiac disease (1).

I usually do not use the term LGS, but the term disturbed intestinal barrier function or increased intestinal permeability. In the end, these are to be understood as synonyms to the term LGS. Entering the term intestinal barrier function in PUBMED yields 2355 publications(https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=intestinal+barrier). If you enter the term intestinal permeability you will get 2054 publications:(https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=intestinal+permeability).

Personal note from me

Based on the available literature, it should be clear to any medical or healing practitioner, even those not familiar with it, that increased intestinal permeability could have something to do with health and possibly the development of disease, if a disorder of intestinal permeability is present.

Of course, this topic is currently the subject of research and there are many open questions. However, established concepts for the successful treatment of Leaky Gut Syndrome have existed for years in holistic medicine and complementary medicine, and it is accepted that this condition can/should be remedied. Finally, every health professional who is primarily interested in the well-being of his patients should come to this conclusion and at least look at treatment concepts from other areas of medicine and, if successful, take note of them with respect. I am a well-trained orthodox physician, internist and gastroenterologist and I have decided – for good reason – to specialise in this subject area. and use it successfully for the benefit of my patients.

In classical medicine, there is currently no feasible way and no concept to deal with such disorders, which cannot be detected endoscopically and with the current methods of conventional medicine. And this is unlikely to change in the short term.

What is the intestinal barrier and what happens in leaky gut syndrome?

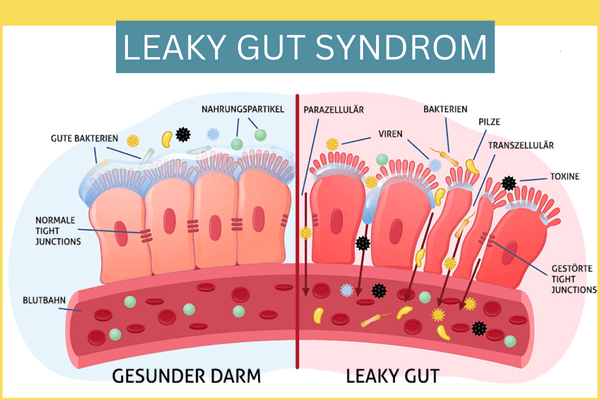

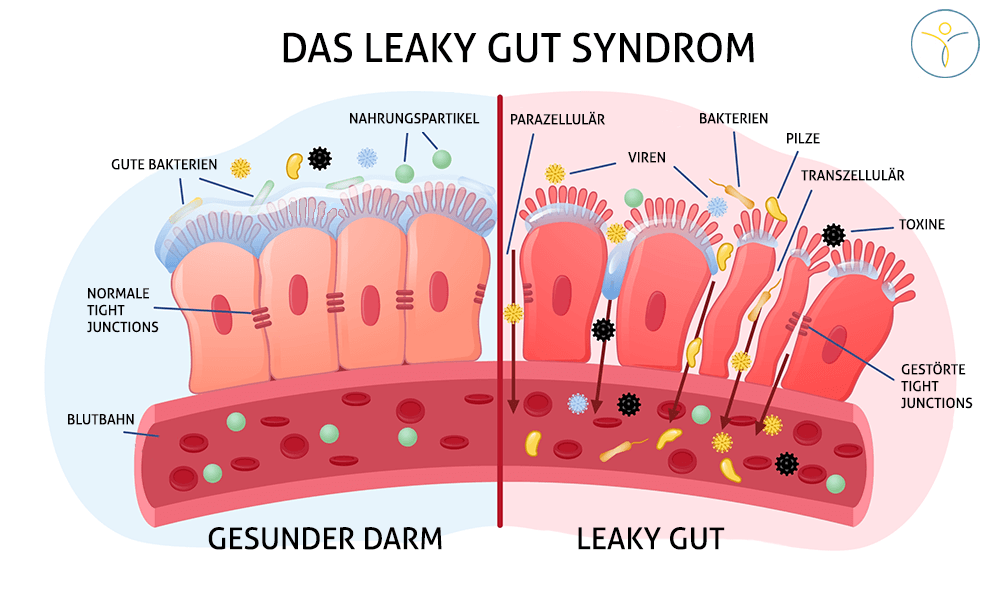

Due to its large surface area, the intestine must protect itself well from possible aggressors (e.g. from pathogenic microorganisms). An intact intestinal barrier, which is composed of different components or layers, serves this purpose. From the outside in, the intestinal barrier is composed of the intestinal flora (the so-called intestinal microbiome, consisting of trillions of microorganisms), the mucus layer (mucus layer), the intestinal wall cells (histologically a single-layered cylinder epithelium) as well as the underlying immune system of the intestine (Note: approx. 2/3 of the entire immune system is located in the intestine = MALT = mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue).

Each layer has its own important tasks in maintaining an intact intestinal barrier e.g. defense against pathogenic microorganisms and preventing their docking and penetration into the intestinal mucosa. At the level of epithelial cells, they are held together by intercellular connections. These are divided into tight junctions, adherens junctions and desmosomes, which together form the so-called “apical junction complex“.

In Leaky Gut Syndrome, there is a disruption of tight junctions and increased intestinal permeability, allowing antigens to penetrate the mucosa and trigger an immune response from the intestinal immune system located there. The tight junctions are weakened by zonulin, for example, which contributes to their dissolution (more information will follow below).

When does leaky gut syndrome occur?

The occurrence of LGS has been well documented in several diseases. These include inflammatory or ulcerative diseases of the intestinal tract, for example, in conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease. It also occurs in patients with celiac disease and gluten sensitivity, intestinal infections and HIV infection or AIDS. Similarly, abnormal intestinal permeability has been described in irritable bowel syndrome (2).

(Read also: What is irritable bowel syndrome?)

Of decisive importance for an intact intestinal barrier are, among other things, a balanced, healthy diet, the avoidance of noxious substances (alcohol, possibly food additives such as e-substances, certain medications such as the group of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) and a reduction in stress levels.

Likewise, unrecognized inflammatory foci in the body, e.g. in the oral and maxillary region, can weaken the intestinal barrier, since pro-inflammatory messengers of the immune system (= cytokines) such as TNF-alpha or interleukin 8 are known to weaken the intestinal barrier. Thus, LGS can also be triggered by pathologies distant from the intestine. In contrast, anti-inflammatory cytokines such as TGF-beta or interleukin 10 can strengthen the intestinal barrier. Through this, we see that the cytokine environment is also of critical importance.

How do we proceed in our practice?

In our anamnesis or diagnostics we find out many things. Among other things, we investigate the present dental materials, test for possible inflammatory foci in the body, check for possible food allergies and additives, for a bacterial overgrowth of the small intestine, for chronic infectious diseases (orthodox medicine focuses almost only on the acute phases of infectious diseases) in the gastrointestinal tract (e.g. Yersinia, Campylobacter jejuni, intestinal parasitoses, etc.), for a possible histamine degradation disorder and a mast cell disease (MCAD). We take a detailed medical history, including a nutritional and social history, and review all previous findings, including existing gastroenterological diagnostics (e.g. breath tests, endoscopies, stool examinations).

Further information on bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine and histamine degradation disorder / mast cell disease (MCAD)

How do we diagnose leaky gut syndrome and what parameters indicate it?

There is currently no practicable gold standard in medical diagnostics that is recognized by all physicians. Unfortunately this often leads to a point of contention with classical medical colleagues, so that I personally would like to see a practicable solution from science and the professional societies as soon as possible. Especially zonulin seems to be a promising parameter for the diagnosis of LGS.

The methods used in research or studies (lactulose/mannitol or lactulose/rhamnose tests) are not practical in everyday practice.

In so-called holistic medicine, the procedure is as follows: stool and blood parameters are determined. It is useful to determine both, as it happens that some values are positive only in stool or blood. In the blood we determine iFABP and zonulin. In the stool we determine zonulin and alpha-1 antitrypsin. You can find more information about the parameters here: https://www.imd-berlin.de/spezielle-kompetenzen/leaky-gut

An excursion into literature and research for those interested in Zonulin

I would like to briefly discuss Zonulin in more detail here, as this parameter is very exciting.

I quote here from an interesting paper I read recently (1):

“Zonulin is able to reversibly open the tight junctions and thereby trigger LGS. The release of zonulin can be induced by pathogenic bacteria, some food antigens, but especially by the wheat components gluten and gliadin, and by pro-inflammatory cytokines.“

Experiments in mice show that overexpression of zonulin is involved in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease and autoimmune disorders. Also, serum concentrations of zonulin were significantly elevated in patients with multiple sclerosis, ankylosing spondylitis (ankylosing spondylitis), rheumatoid arthritis, and type 1 diabetes compared with concentrations in healthy volunteers.

In human clinical trials, larazotide acetate (note: larazotide acetate is a zonulin antagonist/opponent) also improved symptoms in patients with celiac disease.

Taken together, these observations support the importance of zonulin as a biomarker of gut permeability and a promising therapeutic target for LGS-associated autoimmune diseases.

Ongoing studies on larazotide acetate can be found here, an extremely exciting subject: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Larazotidacetat

Also, administration of larazotide acetate significantly improved the so-called multisystemic inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) as supportive therapy to standard therapy (3). The MIS-C, which occurred here after SARS-COV 2 infection, improved with stabilization of the intestinal barrier. Note from me: In my opinion, it can be seen here that zonulin or an LGS can trigger systemic inflammation. This is also understandable, since 2/3 of the immune system is located in the intestine.

Leaky Gut Syndrome YouTube Video

The video is loaded from YouTube and played back after clicking Play. For this purpose, your browser establishes a direct connection to the YouTube servers. Google’s privacy policy applies.

The symptoms of leaky gut syndrome

An LGS is not actually a disease, but a condition of the intestinal barrier, which is associated with various diseases. It is necessary to look for these diseases, treat them and then thereby optimize the intestinal barrier. Of course, this can be supported by various substances that lead to a regeneration of the intestinal mucosa (more on this under treatment options).

Possible symptoms, which can occur with a LGS, are:

- Digestive problems such as flatulence, diarrhea or constipation

- Fatigue and lack of energy

- Food intolerances

- Skin problems like acne or eczema

- Joint pain and inflammation

- Memory problems and concentration difficulties

- Increased tendency to autoimmune diseases and

- inflammatory diseases

Treatment options – Leaky Gut Syndrome

We look for the underlying diseases and treat them causally. A LGS can have many causes, which all have to be investigated when a LGS is present.

An example from my practice: LGS was present along with a bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine (SIBO). Similarly, there was a lamblial infestation of the small intestine. Here we causally treat the lamblia infection by a combination of conventional medicine and natural substances.

In parallel, we carry out a mucosal stabilization phase, an elimination phase of pathogenic microorganisms and a build-up phase of the intestinal flora with natural substances.

This is accompanied by a nutritional diet. This special diet is composed of a complete and strict renunciation of dairy products of any kind and gluten for at least 3-4 months, as those foods are often triggers for LGS. Due to the SIBO, a low FODMAP diet is implemented for 6 weeks, which leads to an improvement for many chronic intestinal symptoms (Read also: SIBO diet plan). After 10-12 weeks, the laboratory parameters, which were previously pathologically modified, are checked again. And the patient returns for check-up.

Individual substances and their effects

The following are some substances that are listed in the medical literature and have been shown to have a positive effect on intestinal permeability based on studies in animals (especially mice) or even humans. Of course, the intestinal flora, the intestinal microbiome (viruses, bacteria, parasites and fungi) and the intestinal immune system must always be taken into account in the therapy. In the following, we focus on the effect of the substances in relation to intestinal permeability.

Glutamine:

Glutamine is an amino acid and very important for the intestinal mucosa. It is also called the “essential amino acid of the intestine” because it is so important for the intestine, although by definition it is counted among the non-essential amino acids. It contributes to the regeneration of the intestinal mucosa. This is also used in conventional medicine if a patient is fed purely by vein so that the intestinal barrier remains intact. Similarly, I have had very positive experiences with patients who had received chemotherapy and got diarrhea from it, through the high-dose administration of glutamine in terms of shortening the duration of diarrhea.

Short-chain fatty acids:

Short-chain fatty acids, e.g. butyrate, have a very positive effect on the intestinal barrier (4). These are produced, among others, by Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a germ found in the intestine. F. prausnitzii produces a microbial anti-inflammatory molecule that strengthens the integrity of tight junctions. Also in patients with Chron’s disease, in whom the germ is often present at a reduced level in the microbiome, F. prausnitzii seems to have a positive effect on inflammation in the intestine through its anti-inflammatory properties and could play an important role in future therapy as a supportive measure (5).

Probiotics:

Some intestinal bacteria, which are also supplied as probiotics, seem to have an optimizing effect on the intestinal barrier, in addition to other positive effects. As an example, the intestinal Lactobacillus spp. produces unique hydroxy fatty acids such as 10-hydroxy-cis-12-octadecenoic acid. In mouse experiments, administration resulted in a strengthening of the epithelial barrier and a strengthening of the intestinal immune system (via increased sIgA secretion) (6,7,8).

Leaky Gut Syndrome – Conclusion

Leaky Gut Syndrome is a serious condition of the intestinal mucosa that needs to be treated and which can precede manifest orthodox medical diseases (even years). An LGS should be a warning signal for any therapist to take action to avert worse. Leaky Gut Syndrome can act both as a consequence of systemic diseases and as a possible trigger, and a connection with autoimmune diseases and chronic inflammatory diseases can no longer be denied.

Many questions are certainly still open, the diagnostics not conclusively clarified and there is still a need for a clearer definition to be made. However, recent studies and investigations show the relevance of the intestinal barrier, not least the promising results obtained by the administration of the zonulin receptor antagonist larazotide acetate.

We can certainly look forward to many future findings from research here, as the topics of microbiome and intestinal barrier are being intensively researched.

Literature / Sources:

1. Kinashi Y, Hase K. Partners in Leaky Gut Syndrome: Intestinal Dysbiosis and Autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2021;12:673708. Published 2021 Apr 22. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.673708.

2. Camilleri M. Leaky gut: mechanisms, measurement and clinical implications in humans. Gut. 2019;68(8):1516-1526. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318427.

3. Yonker LM, Swank Z, Gilboa T, et al. Zonulin Antagonist, Larazotide (AT1001), As an Adjuvant Treatment for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children: A Case Series. Crit Care Explor. 2022;10(2):e0641. Published 2022 Feb 18. doi:10.1097/CCE.0000000000000641

4. Kelly CJ, Zheng L, Campbell EL, Saeedi B, Scholz CC, Bayless AJ, et al.Crosstalk Between Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Intestinal Epithelial HIF Augments Tissue Barrier Function. Cell Host. Microbe (2015) 17:662–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.005

5. Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(43):16731-16736. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804812105

6. Kishino S, Takeuchi M, Park SB, Hirata A, Kitamura N, Kunisawa J, et al. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Saturation by Gut Lactic Acid Bacteria Affecting Host Lipid Composition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2013) 110:17808–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312937110 74.

7. Miyamoto J, Mizukure T, Park SB, Kishino S, Kimura I, Hirano K, et al. A Gut Microbial Metabolite of Linoleic Acid, 10-hydroxy-cis-12-octadecenoic Acid, Ameliorates Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Impairment Partially Via GPR40-MEK-ERK Pathway. J Biol Chem (2015) 290:2902–18. doi: 10.1074/ jbc.M114.610733 75.

8. Kaikiri H, Miyamoto J, Kawakami T, Park SB, Kitamura N, Kishino S, et al. Supplemental Feeding of a Gut Microbial Metabolite of Linoleic Acid, 10- hydroxy-cis-12-octadecenoic Acid, Alleviates Spontaneous Atopic Dermatitis and Modulates Intestinal Microbiota in NC/nga Mice. Int J Food Sci Nutr (2017) 68:941–51. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2017.1318116